People who know me know that the most significant event in my professional ( and personal!) life happened in 1979 when I was forced transferred to Simon Gratz High School. It was a racial transfer, ordered by the now defunct HEW, designed to racially "balance" the faculties of schools within segregated districts receiving federal dollars.

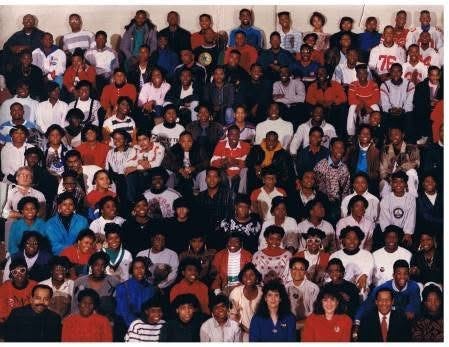

The transfer occurred mid year and upended the lives of over 2000 teachers mostly young, and of course the tens of thousands of students who would lose beloved teachers they counted on seeing each day replaced instead by strange faces. And because the transfers were based on race and seniority, in a segregated city, it was mostly young black and white teachers who were ripped from their neighborhood schools and sent to ones outside of their own communities.

I was teaching at a junior high school in a white working class neighborhood when the reassignments occurred. When it was my turn to select a school from the list ( designated with "C" for Caucasian or "N" for Negro -- I kid you not. -- that was their verbiage in 1979 and do note that Latino and Asian were "O" and didn't count in the racial mix) I chose Simon Gratz.

I was 26 years old and admittedly ( and shamefully) terrified. I chose Gratz because I knew where it was and how to get there by public transportation but everything else I "knew" about Gratz scared me to death. It was the first Philadelphia public high school to become racially isolated in the 60s with a nearly all Black student population. I heard of it when I was in high school up in the Far Northeast in a very white enclave and the reports were very mixed- confusing to me and contradictory. It had a reputation for violence ( Gratz is for rats!) but it also was the site of immense Black pride. For a time Swahili was taught there and in the late sixties, under the leadership of Marcus Foster who was then principal ( soon to become famous as the Superintendent of Oakland schools assassinated by the SLA - the same group which kidnapped Patty Hearst ) students marched to the Board of Education Building demanding that African American History be taught in schools. They were met by Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo's thugs with batons and hoses.

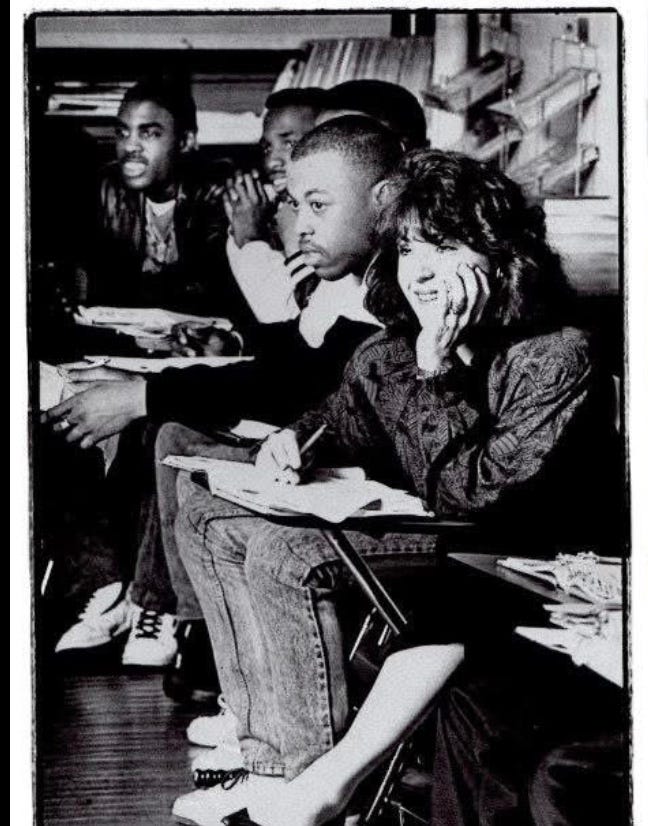

My first weeks at Gratz were challenging. I had never taught high school before so the kids seemed REALLY REALY big! I had never taught in such a large building before and I often got lost. And I had never been in an environment where I was the only white person in the room.

There are so many stories about what I learned from being a teacher at Gratz. And even today, nearly forty years later, through my long term relationships with former colleagues and students, I continue to learn from and with them in these times.

Here's the story I'd like to tell today. It happened on my first week at Gratz. I was walking through the hallway between classes and a young man I didn't know came up beside me.

"You new here?" he asked?

I forced a smile and tried to appear teacher-like.

"How can you tell?" I asked sincerely wanting an answer.

He paused, looked at me as a wide smile spread across his face, until he burst into laughter.

"Because you look like you're scared to death!!!"

His laughter echoed in the marble hallway, as I caught a glance of my reflection in the marble wall -- a scared white girl, clutching her purse and brief case close to her body.

It was a shameful moment for me, for sure. But it was also transformative. I saw myself through my students' eyes and it was not a pretty sight. And I understood in an instant that one could never teach people who instilled fear in you.

All you would be teaching them is your fear.

As the days and weeks of that first semester at Gratz turned into months, I began to do what I had never been taught how to do in any of my education classes - I interrogated my own fear.

Where did it come from? What did it mean? How could I move past it? What didn't I know that I needed to know in order to be an effective educator of African American adolescents in the last decades of the 20th century?

What makes me so angry and sad this particular February - at the beginning of Black History month is the war on Diversity and Equity being spearheaded by the new administration. trump and his minions have struck Black History Month ( along with Women's History Month and Holocaust Remembrance Day) from federal calendars and some states have passed laws limiting what teachers can teach about the history of race and racism.

This will insure the continuation of ignorance for yet another generation.

My initial fear of my students was the fear of the unknown. As a certified English teacher with a BA in Literature from Pennsylvania State University in 1973, I had not been required to take one course in Black literature, arts, culture or history. Things weren't any better in my M.Ed program at Temple University in 1974, located down the street from Gratz in the heart of the African American community.

And while I recognized my lack of preparation for my position at Gratz, it took several years for me to re-educate myself to be a better mentor/teacher to my African American students. I signed up for workshops and seminars in African history and culture. I took classes in Black Literature, the Harlem Renaissance and Black Arts and Black Theater. I read W.E.B. Dubois, Carter G. Woodson, Lerone Bennet Jr, and other Black scholars and historians. I read novels, plays, memoirs and poems by Black men and women and brought all of those texts into my English classroom.

My students and I were discovering these texts together and in opening up discussion about the themes and characters in the works, I got to see the rich and complex ways in which culture and history intersect with individual personal lives and how power is transmitted and utilized through systemic institutional racism throughout this country's history. It became clear to us that enslaved people from Africa were not "tabulae rasae" but came here with hundreds of years of a civilization's patterns and values which were central to every aspect of Black life here from music to language to religion.

It was a very expansive time in my life. In the process of re-educating myself, I became connected with other educators of different races and ethnicities all working to bring Black history and culture to life in the classroom. There were my colleagues in the Philadelphia Writing Project were we created spaces for "hard talk" about race in a setting of trust. There were the artists and writers of the Philadelphia Young Playwrights Festival who created space in classrooms for students to turn their life experiences into theater - reversing the expert-novice relationship between teacher and student. In that world, my students were teaching me about their lives and I learned how to give them the tools to put it on stage.

When I retired in 2008, I began work on a play of my own -- a one woman show that tells the story of one teacher's coming of age into a recognition of racism, its history and the insidious and multigenerational impact of systemic racist laws and policies on children in American classrooms. Before that, I taught graduate school to experienced and prospective teachers where we explored these themes together. And today, I feel a great sense of gratitude for so many of my former students who have made teaching their life's work.

Once, one of my former students asked me if I would have become as progressive in my politics if I had not been forced transferred to Gratz.

"Hey Ms. Pincus! What do you think you would be like if you transferred to a suburban school? Do you think you'd be all preppy and elitist?"

I'd like to think that I wouldn't have been. I'd like to think that my innate curiosity and sense of justice would have been activated by interrogating the privilege I'd be part of. Would I have paid any attention to the funding discrepancies between wealthy suburban districts and urban ones? Would I have questioned the choice of required texts or would I have robotically taught the literary canon ( sans minority or women writers) from the same lecture notes I took from my Penn State professors?

Perhaps not.

People learn when there is a "felt need." Where did my "felt need" to learn Black History come from?

It came from my African American students. It came from my confronting and working through my fear, ( which was based on ignorance and inherited racist beliefs ) getting to know my students as beautiful, complex, diverse and dynamic human beings and caring deeply for their well-being and potential growth.

It came from listening, and questioning, and finding knowledge and joining communities and learning together.

There's another part to this story -- the unexpected gift that my students gave me a few years into my re-education journey.

One day after finishing our work with "Fences" a student randomly called out, "Yo, Ms. Pincus. What are you? I mean who are you?"

"What do you mean?" I replied nervously.

"Who are YOUR people? You've been spending so much time teaching us about our history and stuff-- what about you? What are you?"

I froze. It was a question I had dreaded and in the past, perhaps I would have avoided answering. But I took a deep breath and said, "I'm Jewish. I'm a Jew."

And instead of the expected barrage of anti-Semitic tropes and myths, this is what I received in return.

"So Ms. Pincus, why don't you teach a book by a Jew? Teach us about your culture."

This is what empathy looks like. It moves both ways, back and forth in the context of a relationship, born from mutual respect and caring.

But one thing must be made clear here. The onus for making this happen is on the teacher -- she is the one with the institutional power. She must understand that and use it wisely for the good of her students.